I’m writing this post from Montréal. In the lead-up traveling earlier this week, I didn’t have time to write a blog post, which broke my regular posting streak. That’s okay, though: traveling has actually given me a chance to think more about what I wanted to write this week, which was a little reflection on how I wrote a poem that recently got published: “Manner” in Hawai’i Pacific Review.

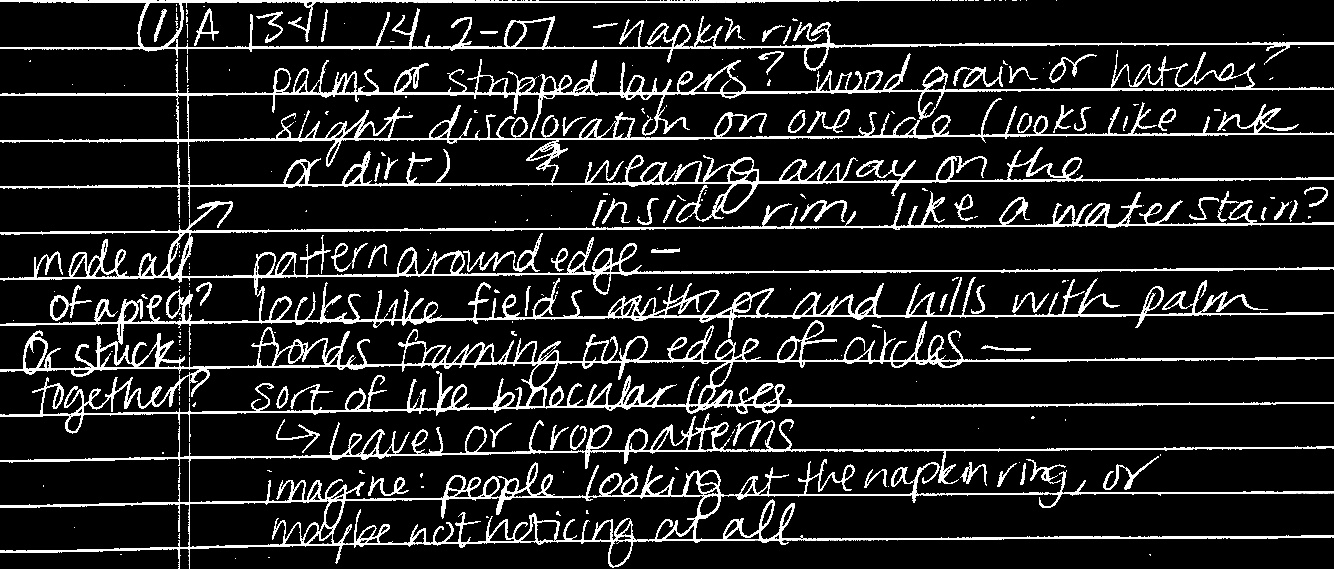

“Manner” was inspired by an item in the University of Nebraska State Museum. Last summer, I picked out a few times from the UNSM Pacific collection, a fairly large collection that contains over 800 items from the Philippines alone. I chose items from a spreadsheet the collections assistant had sent me, and I ended up with a selection of everyday objects and ritual items. Then, I spent a few hours viewing the items closely. I jotted down my observations (some of those notes are the header image for this post), and took photos of the objects from different angles with my phone. The item that inspired “Manner” was a napkin ring, one of a set, and the spreadsheet listed as part of the item’s provenance: “made by convicts in Linguan Prison.”

The napkin ring is about an inch or 1.5 inches in diameter, and maybe an inch tall. What made its appearance so remarkable was the intricacy of the design. It wasn’t particularly florid or detailed, but the fine lines and clean carving implied the delicacy with which someone constructed it. It’s somewhat startling to realize, then, that this is an item that was made with prison labor. This is not some small-batch, artisanal, fair trade product made by someone who is free to practice their craft; this was made by someone who was not free to choose otherwise.

The first draft of “Manner” came out quickly, and many of the initial lines are intact, which you can see below in the image of the handwritten draft. The poem is a kind of ekphrasis in that the artifact itself is described in the lines of the poem, though what’s maybe different about this is that the actual detailed description of the item wasn’t the first thing I wrote in the poem. The lines that describe the napkin ring—”The scene / on the ring is a sunrise over / rolling fields of what must be / rice or other grain,” etc.—were added when I realized that this dinner scene I was envisioning needed more vivid images. It wasn’t immediately apparent that I was writing about a specific napkin ring, but I didn’t want to go the route of including an epigraph, or do anything else that would make that association too explicit. You can also see in the handwritten draft that the title was first just the museum’s labeling convention, and I was playing around with the idea of including “After Vern Rutsala,” since I was also thinking about Vern Rutsala’s “Good Guests” while writing this. Both of these things felt inert: the impersonal naming convention, and the vagueness of the “after” didn’t feel like it was adding to the poem.

But what might make this poem a different flavor of ekphrasis is that the artifact is being used in the poem. When I think of ekphrasis, I think of poems that focus on the scene on display in a piece of art; any motion in a poem is the motion of a painting’s or sculpture’s subject. In an ekphrastic poem about an artifact, the thing that’s being described is a thing that can be used.

This is one of the reasons why I love using the exhibits in a natural history museum as basis for poetry. I can—and have—written ekphrastic poems based on art, but I think I sometimes get so caught up in how a piece of art is made that every ekphrastic poem I write in this way becomes an ars poetica. Which, you know, is fine, but a natural history museum helps me do more than write poetry about poetry. Instead, I feel like I write in a register where a poem feels more visceral.

I also have complicated feelings about natural history museums in particular; while I may find them fascinating and inspiring, I also feel very critical of them. Being in a natural history museum makes me think about the impulse to collect, to amass collections, to present items of vital importance to one person or group’s way of life as mere curiosities. That gives more energy to the poems I write; the poems I find most pleasurable to write and to worry through are the poems that give me something to worry about.

So I’m in Montréal for this conference, and something I tried to do while here was to visit at least one museum and start writing one more poem. My hotel is near McGill University, and there’s a natural history museum—the Redpath Museum—on campus that’s one of the more affordable tourist attractions since admission is pay-what-you-can donation-based. The Redpath boasts an eclectic collection of exhibits. My favorite exhibit was a glass case titled “Une Énigme pour le Conservateur—A Curator’s Conundrum.” It features a partial head of a statue of unknown provenance, and the case explains the process of puzzling out an object’s origin. This kind of detective work is something I love to do.

The poems inspired by the few hours I spent in the Redpath are rough and not yet fit for public consumption, but those poems are the first poems I’ve tried to write in a while. They’re also poems that are continuing a trend I’ve noticed with my writing, which is that I’m editing much more, and much more rigorously. If left to my own devices, I am the type of writer who will draft endlessly, but not drafts of the same piece: new drafts of new pieces until I stumble into writing the one piece that just sounds right on the first try. My writing education has been slowly changing this habit. In grad school, I can’t always just write new things. Time prohibits me, but also, if the workshop has been generous enough to give thoughtful feedback, then I should be grateful and consider that feedback closely.

It is also a much healthier approach to writing, and in life: I can’t just start over from scratch whenever I feel I’ve done something wrong.

This way of writing also turns craft into a puzzle, like the act of putting together a picture of an unknown object’s origins with the help of different experts. Some poems, like “Manner,” begin very quickly. Others take a long time and many iterations, but it’s always worth the work to get it right.