Little thoughts about learning, living, and writing.

Subscribe to stay updated.↓

-

Drafts and daydreams

My partner and I were talking the other day about how we form thoughts, and I mentioned that my thoughts are not images or sounds or sentences, but are words that I feel in my mouth. I don’t visualize writing in my mind’s eye…because I don’t have a mind’s eye. And so anything I think is something I feel like saying.

But, perhaps paradoxically, I am not generally a talkative person. My college and university professors have lamented this. You could not pay me to start a class discussion. Though I assign presentations to my students (and generally know the pedagogical benefits of presentations), I will avoid presentations myself as much as possible. If left to my own devices, entire days can go by without my saying a word. It’s not that I don’t have anything to say. I just write everything down instead.

This afternoon I started writing through the last pages of the journal I’ve been keeping for the past 30 days. I filled this notebook much faster than I anticipated: I think I only missed one day of writing this past month. Most days, I wrote through several pages. This journal was a mix of daydreams, notes about books I read, drafts of stories and poems.

The fact that I wrote through so quickly is one of the reasons I’ve stopped indulging my notebook fancies. Though the Leuchtturm1917 hardcover A5 is the perfect notebook (this is not an ad—I just like the notebook), I unfortunately cannot justify dropping $17 per notebook on something that will only last me a few weeks. The solution to this might be “Write less.” But if there’s such a thing as writing too much, then I am probably doing it.

But what am I doing with all this writing? Because I’m rarely sharing it. My daydreams and drafts are hardly worth remarking on. Most of the time I’m pretty vague, running purely on feeling big feelings instead of thinking deep thoughts.

This isn’t anything new. Among the things I did today was look through a notebook I kept this time ten years ago. I was in my last year of undergraduate, unhappy and stressed (mostly self-inflicted). Ten years ago I approached journaling much differently in some ways. My journals were more so a record of events. My typical day involved attending (or skipping) class, working my part-time job at the resource center of a freshman dorm, holding down an (unpaid) internship, and stressing out about what I was going to do after graduation.

But in other ways, my journaling is exactly the same—pure stream-of-consciousness. I wrote down minute-by-minute countdowns to the end of my work shifts. I drafted some awful poetry. I daydreamed about my friends and I getting everything we wanted, everything we worked for. My chemistry notes were filled with doodles of trees. Occasionally, there’s a spark of something in that ten-years-ago notebook. (Early in that notebook, I wrote, “Already there are people who grew up believing that this is the status quo when it shouldn’t be.” I was talking about the need for publicly financed elections, but really, take your pick.) Occasionally I come across an entry and a memory presses against the back of my teeth, and I’m back in New York, curled into myself and hanging on tightly to the parts that threatened to disperse.

And really, what other reason for me to write, except to remember?

-

In the middle of reading

It is, obviously, good practice to wait to write a review of a book until after you’ve read it. Waiting to review a book until after you’ve read it means that you’ve given the book a fair shot. You’re able to speak intelligently about the work as a whole. You avoid cherry picking information from the book and taking things out of context. Reading a book in its entirety is an important step to making sure you have all the information before you pass judgement. to review a book, you must, obviously, read it first.

And so I feel it is necessary to say that this blog post is not a book review. I am in the middle of reading this book—Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters—and I have some thoughts about it, but less about the book itself and more about the experience of how I am reading it. I will cherry pick. I will not speak intelligently about the book, probably. But I’m having a weird reading experience and I want to tell you about it.

When I went to mark this book as currently-reading on Goodreads, I skimmed through some of the reviews. At the top was Roxane Gay’s succinct 4-star review. Then there were quite a few 1-star reviews that wrote about the book’s misogyny, the disgust that people felt as they were reading it, and one person’s review homed in on the line “After all, Every woman adores a Fascist” (p. 57). Reading these reviews influenced my mindset going into the book. The novel’s synopsis sounded so intriguing. Before I even started reading I imagined it might be a comp title for one of my own works-in-progress, a novel that, if done right and written in the way I want it to be read, might ruffle some feathers.

Seeing these Goodreads reviews, I found myself somewhat on the back foot. What was I getting myself into? What was this book actually going to be about?

I’m still in the middle of reading the novel. I’m finding myself reading a bit slower than usual, partly because I’m having a busy week and haven’t found much time, and partly because the 1-star reviews have made me want to read slower, more carefully. The context of that Fascism line is—surprise, surprise—more complex. One of the novel’s main characters, Reese, is in an abusive relationship with a man named Stanley. Reese is a trans woman who has seemingly little of the stereotypical angst of transition; she has, at that point in the story, been transitioned for some time. I don’t think there had been any discussion of her life pre-transition in the beginning of the novel. She has always been Reese, a woman. All of her actions, then, read more like she is trying to convince other people of her womanhood. Her relationship with Stanley is an extension of that. Immediately after the Fascism line, the narration continues on to say that “Reese spent a lifetime observing cis women confirm their genders through male violence. Go to any schoolyard. Or just watch your local heterosexuals drinking in a bar” (p. 57). These observations are the same ones many feminists point out about patriarchy writ large, though in Reese’s case these observations are reified and used as confirmation of her own gender identity.

It’s important to point out, however, that this line comes up eight years before the main events of the story.

In the main story line—the “present” story line— of the book, Reese has broken up with Amy, her girlfriend who had detransitioned to a person named Ames. They had been broken up for some time when Ames impregnates Katrina, a woman who is his boss, and in trying to convince Katrina to keep the baby proposes an unconventional parenting trio with Reese, who deeply—almost desperately—wants a child. This story line alternates with the events of eight years ago when Reese and Amy met and entered into a relationship. But the “eight years before conception” time stamp that marks these sections is somewhat misleading, because many of the events happen even further back, all the way to Amy’s high school and college years. In doing so, the book covers the rapid way culture changes, particularly culture around transition, and all the growing pains associated with that change. Alternating between past and present puts different points in the cultural milieu next to each other as a way of showing just how much has changed in the short span of eight years. Eight years is the length of time comprising freshman year of high school through senior year of college (for U.S. students who follow that conventional path). Eight years is the same span of time as two U.S. presidential terms—think how much can change in a short instance.

And so a line like “Every woman adores a Fascist,” is, in any context, wildly misogynistic. But that line comes from the mind of a character who is misogynistic at that stage in her development as a person. Reese is not likable. She is mean as hell, to say the least. But throughout the rest of the book, I don’t think that Reese is that person who thinks every woman adores a Fascist.

I’m halfway through reading and I have no idea where the ride is going to take me. I don’t think I would feel compelled to write a blog about the experience of reading this book if I didn’t notice how much difficulty I was having reading this book. Not because it’s particularly confusing or unreadable, but because I have these different constituencies in my head offering opinions and muddying my experience of the text as it is. Normally I’m perfectly fine being “spoiled” for a story; if the thrill of a story depends so much on the withholding of some pivotal plot point, then some part of me believes that the story won’t have that much staying power. This time around, I’m realizing that spoilers have nothing to do with the events of a story and everything to do with the mental and emotional experience of encountering a story without being influenced by the opinions of other people. I sometimes think about those Goodreads reviews I skimmed and I wonder: did we read the same book? Am I having the same experience that those readers did?

Anyway, I’m excited to keep reading. This blog post is not a review; I think I’ll have more to say once I’ve finished.

-

How I wrote, and how I am writing

I’m writing this post from Montréal. In the lead-up traveling earlier this week, I didn’t have time to write a blog post, which broke my regular posting streak. That’s okay, though: traveling has actually given me a chance to think more about what I wanted to write this week, which was a little reflection on how I wrote a poem that recently got published: “Manner” in Hawai’i Pacific Review.

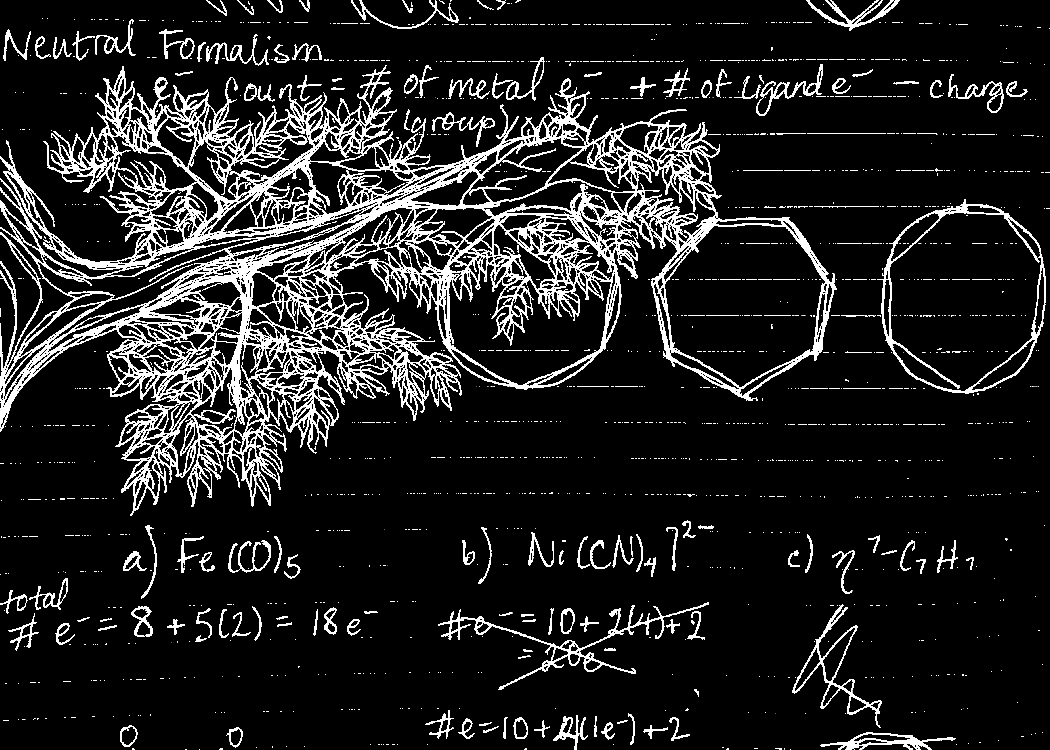

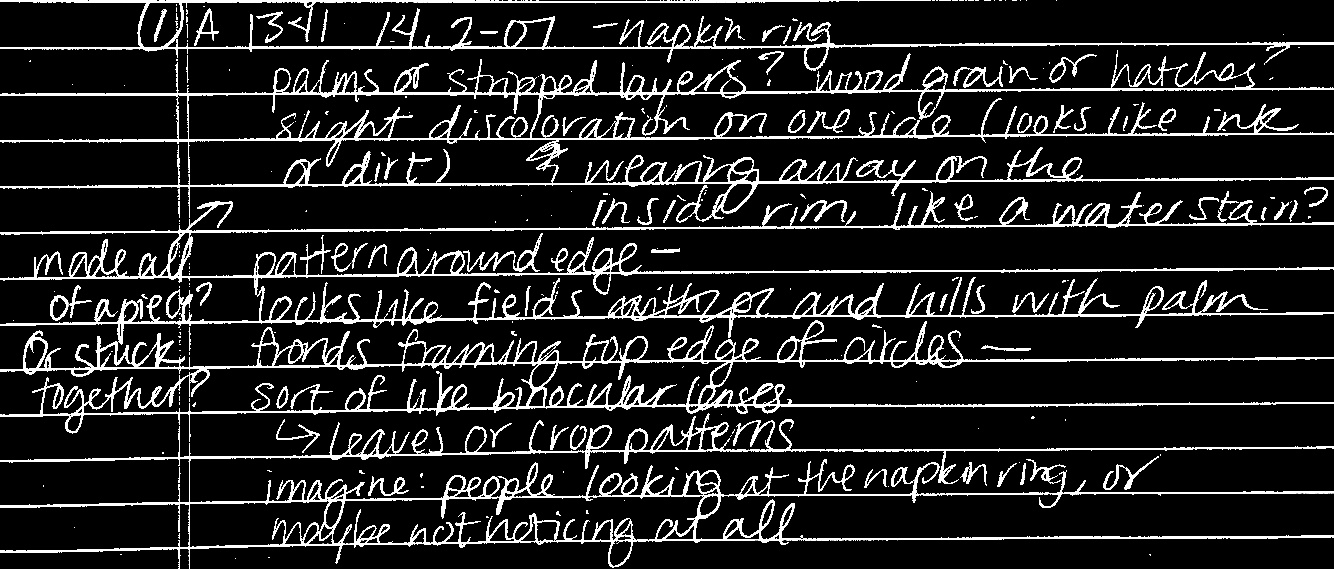

“Manner” was inspired by an item in the University of Nebraska State Museum. Last summer, I picked out a few times from the UNSM Pacific collection, a fairly large collection that contains over 800 items from the Philippines alone. I chose items from a spreadsheet the collections assistant had sent me, and I ended up with a selection of everyday objects and ritual items. Then, I spent a few hours viewing the items closely. I jotted down my observations (some of those notes are the header image for this post), and took photos of the objects from different angles with my phone. The item that inspired “Manner” was a napkin ring, one of a set, and the spreadsheet listed as part of the item’s provenance: “made by convicts in Linguan Prison.”

The napkin ring is about an inch or 1.5 inches in diameter, and maybe an inch tall. What made its appearance so remarkable was the intricacy of the design. It wasn’t particularly florid or detailed, but the fine lines and clean carving implied the delicacy with which someone constructed it. It’s somewhat startling to realize, then, that this is an item that was made with prison labor. This is not some small-batch, artisanal, fair trade product made by someone who is free to practice their craft; this was made by someone who was not free to choose otherwise.

The first draft of “Manner” came out quickly, and many of the initial lines are intact, which you can see below in the image of the handwritten draft. The poem is a kind of ekphrasis in that the artifact itself is described in the lines of the poem, though what’s maybe different about this is that the actual detailed description of the item wasn’t the first thing I wrote in the poem. The lines that describe the napkin ring—”The scene / on the ring is a sunrise over / rolling fields of what must be / rice or other grain,” etc.—were added when I realized that this dinner scene I was envisioning needed more vivid images. It wasn’t immediately apparent that I was writing about a specific napkin ring, but I didn’t want to go the route of including an epigraph, or do anything else that would make that association too explicit. You can also see in the handwritten draft that the title was first just the museum’s labeling convention, and I was playing around with the idea of including “After Vern Rutsala,” since I was also thinking about Vern Rutsala’s “Good Guests” while writing this. Both of these things felt inert: the impersonal naming convention, and the vagueness of the “after” didn’t feel like it was adding to the poem.

The first draft of “Manner” taken directly from my notebook. But what might make this poem a different flavor of ekphrasis is that the artifact is being used in the poem. When I think of ekphrasis, I think of poems that focus on the scene on display in a piece of art; any motion in a poem is the motion of a painting’s or sculpture’s subject. In an ekphrastic poem about an artifact, the thing that’s being described is a thing that can be used.

This is one of the reasons why I love using the exhibits in a natural history museum as basis for poetry. I can—and have—written ekphrastic poems based on art, but I think I sometimes get so caught up in how a piece of art is made that every ekphrastic poem I write in this way becomes an ars poetica. Which, you know, is fine, but a natural history museum helps me do more than write poetry about poetry. Instead, I feel like I write in a register where a poem feels more visceral.

I also have complicated feelings about natural history museums in particular; while I may find them fascinating and inspiring, I also feel very critical of them. Being in a natural history museum makes me think about the impulse to collect, to amass collections, to present items of vital importance to one person or group’s way of life as mere curiosities. That gives more energy to the poems I write; the poems I find most pleasurable to write and to worry through are the poems that give me something to worry about.

So I’m in Montréal for this conference, and something I tried to do while here was to visit at least one museum and start writing one more poem. My hotel is near McGill University, and there’s a natural history museum—the Redpath Museum—on campus that’s one of the more affordable tourist attractions since admission is pay-what-you-can donation-based. The Redpath boasts an eclectic collection of exhibits. My favorite exhibit was a glass case titled “Une Énigme pour le Conservateur—A Curator’s Conundrum.” It features a partial head of a statue of unknown provenance, and the case explains the process of puzzling out an object’s origin. This kind of detective work is something I love to do.

The poems inspired by the few hours I spent in the Redpath are rough and not yet fit for public consumption, but those poems are the first poems I’ve tried to write in a while. They’re also poems that are continuing a trend I’ve noticed with my writing, which is that I’m editing much more, and much more rigorously. If left to my own devices, I am the type of writer who will draft endlessly, but not drafts of the same piece: new drafts of new pieces until I stumble into writing the one piece that just sounds right on the first try. My writing education has been slowly changing this habit. In grad school, I can’t always just write new things. Time prohibits me, but also, if the workshop has been generous enough to give thoughtful feedback, then I should be grateful and consider that feedback closely.

It is also a much healthier approach to writing, and in life: I can’t just start over from scratch whenever I feel I’ve done something wrong.

This way of writing also turns craft into a puzzle, like the act of putting together a picture of an unknown object’s origins with the help of different experts. Some poems, like “Manner,” begin very quickly. Others take a long time and many iterations, but it’s always worth the work to get it right.

-

Pushed Output

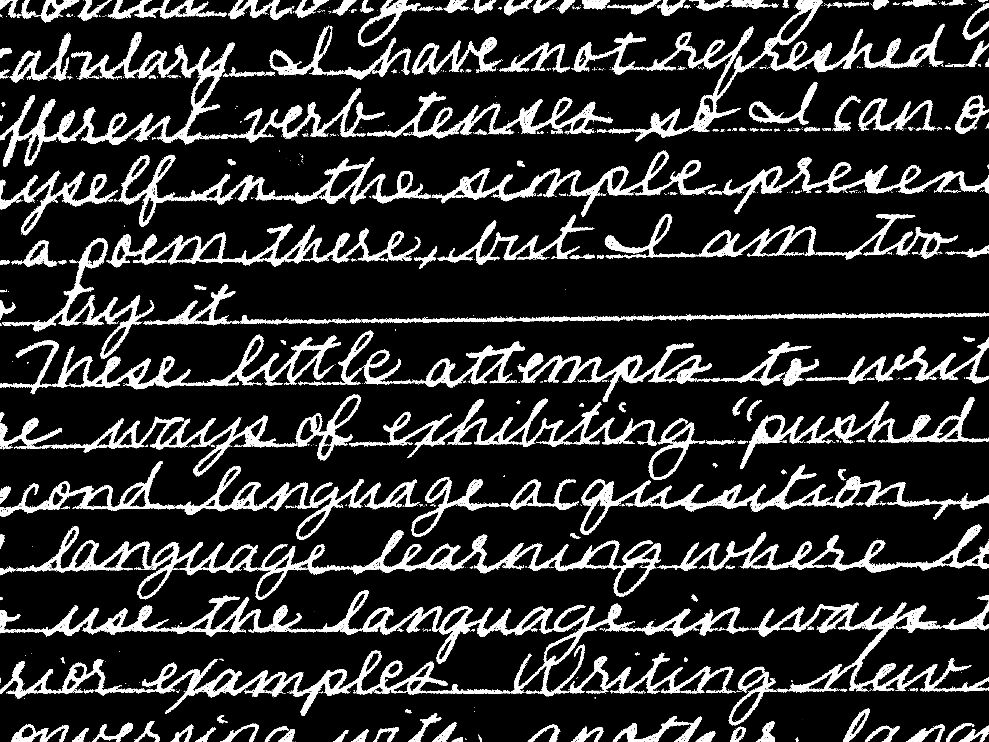

Lately, I have been trying to write a few sentences each morning—a paragraph, if we’re being generous—in French to practice reading and writing in the language. My attempts are slow, messy, and probably grammatically incorrect, and my vocabulary couldn’t possibly be more sophisticated than an elementary school child’s vocabulary. I have not refreshed my memory of the different verb tenses and conjugations I learned in high school, so I can only express myself in the present tense.

These little attempts to write in French are ways of practicing “pushed output.” In second language acquisition1 studies, pushed output is the part of the language learning environment where learners try to use the target language in ways it would naturally be used in everyday use, and in ways that deviate from prescribed formulas. Writing new sentences, or conversing with another person in the language to practice speaking extemporaneously—these are examples of pushed output. If you have ever wondered why any language-learning class involves conversation time, it is because instructors are building in time for pushed output.

Of course, these learning concepts are not limited to second language acquisition; it can be useful for anyone to further refine their first language(s). In my own classroom, I encourage pushed output through class discussion, writing prompts, and other activities in which my students are actively working with language and their writing. It’s not enough just to read examples of good writing, but to take it apart and put it together again. It’s not enough to just listen to me point out the structure of an assigned piece, but for my students to get into the heart of the writing themselves.

Lately, I have been having trouble motivating myself to push some output in my first (and so far only) language: English. AWP was a great shot of energy in some ways, but the weeks since then has been somewhat overwhelming, making me really drag my feet through my days. I’ve been a bit sick (’tis the season for mysterious viral illnesses to spread, I suppose) and moving slowly as a result. My creative projects have stalled. My teaching work has been dragging. All this can be explained in part by the underlying fact of my feeling physically unwell. But what about the other parts? The parts that have, in the past, made me feel better because I could write? What happens when I cannot push output?

Five environmental2 elements that “contribute (but do not guarantee) optimal L2 learning are: acculturated attitudes, comprehensible input, negotiated interaction, pushed output, and a capacity, natural or cultivated, to attend to the language code, not just the message.” These are somewhat intuitive: in order to learn a new language, you have to have some kind of affinity for or interest in the language, you have to be exposed to clear messaging in that language, you should interact with people who speak that language, you have to seek opportunities to use the language, and you have to develop a sense for how the language works (its grammar, etc.), not just be able to understand the meanings of communication in that language. My pushed output has stalled; can I find ways to bolster the other elements? How can I cultivate my attitude towards writing? What comprehensible inputs can I (re)visit? Who can I have a negotiated interaction with about writing? How can I keep growing my capacity to attend to the language code?

I don’t have very many answers; lately it feels like I never do. But sometimes I find it useful to pause and think through the ways in which writing falls into these environmental elements of language learning. I forget, sometimes, that I am still learning my first language. I use it so often, and have become immersed in my learning of it, that it has become something like instinct. But it’s not quite instinct. There will always be more to learn. I will always have to maintain a steady practice of learning.

Notes:

- This term is somewhat debated; oftentimes, when people learn another language it can be their third, fourth, fifth, etc., language that they are trying to learn. “Second language acquisition” seems to be a fairly widespread shorthand to communicate the concept of learning a language aside from the first one(s) you learned as a child; “L2” then refers to the “target language,” or the language other than the first that is being learned. The concepts I’ve learned, and the ones I reference in this blog, come from the textbook of the SLA course I took one summer: Second Language Acquisition by Lourdes Ortega, 2013, Routledge.

- Ortega, p. 79. “Environmental” factors don’t refer to the place/ecology, but are a metaphor for the language-learning space.

-

Post-AWP thoughts

The last time I attended AWP1 was in 2020, the ill-fated San Antonio year. At the time, I decided that that experience was all I would need of this particular writing conference. It was a weird year, small because so many people had decided not to attend (since AWP had not made the decision for them by canceling the conference when COVID began to spread precipitously), but I was already overwhelmed. I only went to a few panels, and most of my time was spent working the table for Flyway: Journal of Writing and Environment. I am not an extroverted person, but at the time I was extroverted enough to call out, “Are you interested in environmental writing?” to get people to stop and talk. I still have memories of one person who had stopped and asked about the capaciousness of our definition of environmental writing (though I, sadly, do not remember the person’s name). I loved the question so much that I yelled, “I love this question!” before launching into a response. And honestly, that was the height of my experience; I wanted that memory to remain untouched, in a way, by other memories of AWP.

All this is to say that I felt my first AWP experience was already enough. I decided that I didn’t really have any desire to go again if I didn’t need to.

But I did need to go this year. It was in Kansas City, well within a reasonable drive’s distance, and I had signed up to work the book fair table for UNL’s creative writing program. I did a similar, occasionally asking people who were walking by if were interested in PhD or MA programs. And I talked with people about their writing. Working the table was a surprising reprieve from the overwhelming nature of the book fair. The panels, too, had this function for me. I wasn’t there to network or buy things. I was there for a breather, and to listen in on some conversations.

This, perhaps, was much of the “value” I got from AWP. Most of my book fair purchases were books that are a few years old, not the latest releases, and my purchases were also pretty limited because I, frankly, don’t have much money. I also didn’t go to any offsite events because there were so many to choose from, and also because the day left me exhausted and wanting to relax in my hotel room. But a few of the panels I attended featured writers reading their work, with a Q and A afterward. And I listened, for the first time in a while, to people’s excellent writing in a quiet, attentive place. And it made me want to write. It made me want to fill in the gaps I perceived, or that the panelists described, in the current literary fabric. It made me think about my writing, my works-in-progress, and how they might already be filling those gaps, I just haven’t put that writing out into the world. I felt refilled, refueled, to pursue my creative work in a way that was different from the solo work of making my way through my comps list.

It wasn’t a perfect conference. AWP isn’t a perfect organization.2 And I ended the week very tired and immensely grateful that my teaching schedule this semester means I only teach on Tuesdays and Thursdays, not Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. But I am also grateful that I got to attend. I am grateful that I got to listen to writers share their work; now that I’m out of course work for my degree, I feel as though my opportunities to hear people read are few and far between.

When I wasn’t at the convention center, I was likely avoiding eye contact with people at the hotel gym or exploring Kansas City with a friend in my PhD program. We took the free streetcar up to the River Market district twice: once to have my ice cream craving thwarted by a long line at Betty Rae’s, and a second time to eat a delicious farm-to-table brunch at The Farmhouse on our last day in Kansas City. I did enjoy the moments when I got away from the convention center. I did (to a small degree) enjoy getting turned around whenever I stepped out of a different exit/entrance to the convention center—because it meant I was out of the convention center. I didn’t get a chance to explore San Antonio all that much when I was there in 2020; I’m glad that I did get to go out into the city and remind myself that there’s more to the world that what does or doesn’t get onto a blank page.

Notes

- For folks who might be unfamiliar, “AWP” refers to the Association of Writers and Writing Programs, and the corresponding annual conference that brings together an estimated 10,000 writers, writing programs, and publishers. From what I understand, it’s the biggest writing conference, and a place where many people make connections to the literary publishing world more broadly.

- Among the ways AWP is imperfect was the response to the statement emailed to panel moderators from the Radius of Arab American Writers. It was at the very least, embarrassing for AWP, and, more harshly, employing the kind of oppressive tactics that AWP purports to oppose. See this tweet thread (I’m still calling them tweets, don’t @ me) for more info.

-

“Remember Professional Ethics”

For the past few months, whenever I’ve started writing in a new notebook (a simple spiral-bound, college-ruled notebook; I am a broke grad student and my usual notebook indulgences must be curbed), I’ve written one of Timothy Snyder’s lessons from On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century on the cover. Just yesterday I filled up lesson/notebook four: “Take responsibility for the face of the world.” I’ve started writing in lesson/notebook five: “Remember professional ethics.”

The description from lesson five reads:

When political leaders set a negative example, professional commitments to just practice become more important. It is hard to subvert a rule-of-law state without lawyers, or to hold show trials without judges. Authoritarians need obedient civil servants, and concentration camp directors seek businessmen interested in cheap labor.

Timothy Snyder. On Tyranny, YouTube series. 12 Oct 2021. URL: https://youtu.be/F75dhfkXjw8?si=ENLP-gUIORYvkgLCAs a college instructor in the U.S. during an election year—one of the biggest years for democracy worldwide—this lesson feels particularly timely. When I am teaching my students how to compose their ideas into thoughtful pieces of expository writing, what is it that I’m really teaching? When I prepare lessons to go over the mechanics of good writing, am I simply passing along a list of rules to obey, or am I inviting students to really wonder why we do the things we do in writing?

The official title of the class I teach is “Writing and Inquiry.” I’ve been working through the latter half, the “Inquiry” half, in my preparations this semester. In a world that has become increasingly difficult to trust thanks to the A.I.-charged proliferation of mis/disinformation, I feel as though part of my intent with the class is to teach both the idea that one must constantly question the world, but also how to question the world (and, related, how to find the right answers to the right questions). Asking questions is a skill; entire classes are dedicated to research design so that people know that the results they get from an experiment actually tests the hypothesis being studied. As an instructor, my hope this semester is that I instill the sense of wonder—and, yes, worry—in my students so that they can guard against the bad ethics of malicious actors.

On another note: if past productivity is any indication, I will finish writing through lesson/notebook five by the time I have to turn in my comps portfolios. Despite my impulse to be unruly, become ungovernable, within the university system, I do have a professional commitment to do good work, precisely because I believe it is a way for me to commit to just practice. Last night, I was rewriting a review of Min Hyoung Song’s Climate Lyricism (the journal I initially wrote it for returned it with feedback; my first attempt was not solid, and I’m glad for the opportunity to write it again). Skimming through it and my notes again reminded me that I must turn my attention to the good work I can do. Song writes in the introduction to the book that climate lyricism is:

…the striving for a practice that insists, as the philosopher and activist Grace Lee Boggs insisted, that thinking should not be separated from doing. Thinking itself is a form of doing, and doing is a form of thinking. Unfortunately, the two separate easily from one another, as in an idyllic thinking or a mindless doing, and so what is needed in response is a consciously created routine that makes each partner to the other.

Min Hyoung Song. Climate Lyricism. Duke University Press, 2022, p. 2.This semester, and all semesters to come, I’m making a conscious effort to return to mindful action. There is so much work to do; I’m reminding myself that I can do it, and that I must.

-

(Re-)reading in context

For my PhD program, we have two choices of qualifying exam to reach candidacy: the written exam option (basically, a timed essay in response to a set of questions set by the committee), or the portfolio option (two collections of work based on two reading lists, which can then be the foundation for a dissertation or a post-grad academic job portfolio). Anecdotally, hardly anyone goes with the written exam since the portfolio can have a life beyond the exam; in keeping with that pattern, I am also doing portfolios, and have been working on them pretty steadily in the new year.

Part of each portfolio is a scholarly essay, and I’ve been focused on the essay for my list of Philippine/Philippine American fiction. I’m still in the drafting stages of this essay, so much of my time is spent rotating through the books on my list and the pages of my notebook as I draft by hand. One of the books I’m writing about is a book I’ve written about before: America Is Not The Heart by Elaine Castillo. If, in the future, there are Castillo scholars who examine her works, I lowkey think I’d be foremost among them. I’ve written about America Is Not The Heart before, both in a previous blog post and in my first scholarly publication. One of my first conference papers used that book, again, in comparison to another book’s use of the 1991 Pinatubo eruption. I’ve taught passages from Castillo’s novel to my classes; I’m likely to do so again until reprimanded.

Earlier this week, I cracked open my paperback copy of America Is Not The Heart with the intention of skimming for how often Castillo mentions the name “Marcos” (as in Ferdinand and Imelda). I wanted just a rough ballpark number and intended to just skip around to the parts that seemed likely to contain the name. In my experience, it’s unusual for an author writing about the Marcos, Sr., administration to explicitly mention the Marcoses the way that Castillo does: without nicknames, without titles, without epithets. I’m still drafting my essay, but it’s shaping up to be, roughly, about the ways authors do or don’t name specific figures in their fiction, especially authoritarian figures. As I was skimming, though, I found myself slip into just reading the book and blazed through the first three sections in an afternoon. One of the reasons why I think I would be a Castillo scholar is because this always happens to me with her writing: I go into a familiar text and end up getting carried away by her words. I’ve read America Is Not The Heart countless times this way. When I finally got around to reading How To Read Now, her collection of essays, I similarly read several of those essays multiple times.

My favorite from How To Read Now is probably “‘Reality Is All We Have To Love,’” an essay which gets its title from a John Berger quotation that is the essay’s epigraph:

La Rabbia [Rage], I would say, is a film inspired by a fierce sense of endurance, not anger. Pasolini looks at what is happening in the world with unflinching lucidity. (There are angels drawn by Rembrandt who have the same gaze.) And he does so because reality is all we have to love. There’s nothing else.

John Berger, “The Chorus In Our Heads,” as quoted in “‘Reality Is All We Have To Love’” by Elaine Castillo in How To Read Now: Essays, 2022, p. 203.I’ll confess that I have no knowledge of Berger nor Pasolini save for what Castillo writes about and the little Wiki-walking I’ve done out of curiosity. There is a lot in this essay that I don’t know: I’ve never read The Turn of the Screw (though I’m convinced to read it based on the case Castillo made for the book’s craft and handling of subject matter), I’ve never read the Berger short story “Woven, Sir”—in general, there’s just a lot I haven’t read. And yet, I’m simultaneously helped by Castillo’s writing to understand the things I do not know, and also made to understand that the texts aren’t specifically the point, but the experience in which those texts are embedded. For all the things I don’t know, I do know what it’s like being the only person of color in a white classroom trying to navigate the critique waters. (Though I must say that I haven’t been the only person of color in a classroom since starting my PhD, and it is a wonderful circumstance that takes some getting used to after years of that not being the case.) I do know what it’s like to write something honest, only to be stonewalled because it’s not what people want to hear. I’m still learning how to not let this deter me; I’ve never been particularly courageous or outspoken. And yet it’s increasingly untenable to keep silent about injustices. As Castillo writes, in a sweeping paragraph comprising a single sentence:

It becomes unsettlingly evident that in the absence of anything resembling justice, an artist’s instinctive respect for silence, mystery, and indeterminacy—the parts of our lives that necessarily and often indefinitely remain diffuse, inexpressible, and elusive; indeed indefinite—can be endlessly malleable, exploitable, to be subsumed in that ‘vertigo of nothingness,’ so that the emotional recognition and respect for, yes, silence, mystery, and indeterminacy can just be as swiftly manipulated to protect the powerful and estrange the vulnerable, keeping a cloud of unknowing around the form, and a cloud of unknowability around the latter, trapping them al in a mystery, a confidentiality clause, a Turn of the Screw for all times.

Elaine Castillo, “‘Reality Is All We Have To Love,’” from How To Read Now: Essays, 2022, p. 222At some point, I’m sure I’ll take on the task of trying to diagram this sentence (something that I’ve become mildly obsessed with lately, probably because I never had to do it in elementary or middle school), but one of the many things I admire about this is that it’s a sentence at the heart of “‘Reality Is All We Have To Love’” that is, itself, the nesting doll of all the topics Castillo takes on in the essay: decolonial work, discerning true justice from the veneer of justice, and the protection and danger of silence. But it’s not a sentence that can be easily isolated from the rest of the essay; to understand all of the layers, one should really read it in context.

NB: I take notice whenever I see people mention that links to books, etc., are affiliate links, so I felt the need to say that the links here are not affiliate links. I just really like Castillo’s writing and felt the need to share. If you do read her work, I’d love to hear your thoughts!

-

Routines, not resolutions

Ten years and some weeks ago, I came across the one piece of new year’s advice that I’ve ever really taken seriously in an article link a friend posted on Facebook: focus on the system and not the goal. In the years since, I’ve come across this same idea in different forms. Don’t Break the Chain. No More Zero Days. CGP Grey’s Theme System. In other words: Routines, not resolutions. Guidance, not goals.

When I found the original article my friend had posted by using the Wayback Machine, I quickly realized that it wasn’t the most earth-shattering piece of writing. It’s your standard listicle with a clickbait-y headline. It’s the kind of source that if one my students tried to include it in their research paper, I’d encourage them to keep digging deeper to examine each of the items in the list to find the underlying research. Whatever merits this particular article held for me were probably more a matter of the person who shared it on Facebook; a friend had posted it, and I trust my friends, right? Plus, I was about to embark on my last semester of undergrad at the time, and was therefore open to any and all advice for self-improvement when three and a half years of college felt like it didn’t quite do it for me.

A lot has changed in the past decade, but one thing that has remained constant is my love of seeing a counter of consecutive successful days go up, to see a row of checkboxes checked, to see a calendar get filled in with days I’ve kept up my habits. Of course, during this same time, my ability to stick to routines has, itself, not quite become routine. Every season there’s something new: a different class I need to learn how to teach, or a new milestone I need to reach in my degree. Then there’s the pandemic. And extreme weather events. And all kinds of big and small disasters that I tell myself are always temporary, but nonetheless have lingering effects. Even when things are “over” and I can return to “normal,” it takes a long time for me to revert to form.

But maybe the one thing I’ve really learned is how to try again. Maybe the one thing that has changed is that I’m much more willing to change what my “normal form” is—more interested in adapting than trying to stay a certain course.

Since it’s winter break, many of the campus facilities have been closed between Christmas and New Year’s, but today the campus gym opened bright and early. While I wasn’t there right at opening, I was there before dawn (not a difficult feat since sunrise is after 7:30am right now, and that’s not the earliest I’ve ever woken up for something). It was my first time visiting the campus gym; though I’ve said to myself multiple times that this season I’ll finally get back into a regular gym habit, there’s always been something in the way: a COVID resurgence (or a new variant), or dangerously low temperatures, or unhealthy air quality. I’m fully aware that any of these things could come back to stymie me once again. Even today’s journey to the gym had the potential to be doomed; the campus recreation center is undergoing some renovations to the locker rooms, and in the past that would have been enough to waylay me again.

Today, though, I was determined. There are practically no students on campus; right now is the perfect time to establish a routine before the gym gets crowded again when people return for the semester. I can figure out where all the equipment is, figure out where the lockers are, figure out what my go-to workout is going to be so that I don’t have to dawdle too much. And today, to ease myself back into exercising, I did a simple workout on an elliptical and a cool-down on a rowing machine. I’m already looking forward to doing something different tomorrow now that I’ve gone and done it once.

Next week I’ll probably find some reason not to go to the gym. Or maybe partway through the semester, when I travel for AWP and then to a comparative literature conference, my routines will be so severely interrupted that I’ll have to start over. But until then, I’ll keep trying. One day at a time.

Here are some other routines I’m trying to pick up this year:

- Blogging biweekly. I sort of got into this habit during the latter half of last year, though I missed a few weeks after Thanksgiving. But I have plans this year for blog posts. I hope to make good on them. (Which means that you, dear reader, have biweekly posts to look forward to.)

- Writing three pages daily. While these can be just free writing, I’d ideally like to write towards a publishable piece of some kind.

- Use my paper planner daily. I love paper planners, but around October of last year I suddenly stopped using mine because I just got so overwhelmed; I felt like I didn’t even have enough time to sit down and write out my schedule once a week. My system wasn’t working, so I’m trying a new system this year with a Hobonichi daily planner. One of my older brothers got me a Hobonichi for Christmas one year, and I’ve wanted to give the daily planner another try.

- Share what I’m reading in some way. This is a fuzzy idea, and I’m not even sure what form this will take (Goodreads? StoryGraph? Bluesky posts? Snail mail to friends?), but I think my prior aspirations to read more have not necessarily yielded results, so I’m changing angles. It’s not just that I’ll read more, I’m going to share more.

What about you? What are some of your routines, aspirational or otherwise?

-

“Encore une fois”

As I make my way through grad school, I keep having moments when I suddenly understand what my past teachers were doing in the classroom. As a student, I had a vague idea that I understood when someone was a “good” teacher and when they were a “bad” one. The middle school social studies teacher who just gave us worksheets to fill out with fill-in-the-blank questions was not a good teacher. The high school English teacher who dedicated class time to reading Shakespeare aloud was a good teacher. The anthropology professor I had while studying abroad did her best to get the students out into the city rather than being solely focused on a classroom experience, and she was a great professor.

So sometimes at the end of the semester, I look back at the assignments I’ve given to my students and ask myself if the work done really reflects the things that I value as an instructor. Did I really have them read closely? Did I really have them creatively respond to the reading I assigned? Did I even assign enough reading this semester? I won’t linger too much on this in this blog post; this semester has comprised a mixed bag of successes and failures, and naturally I linger on the multitude of ways I’ve failed more so than the ways I’ve succeeded.

The summer before last, I took a class in second language acquisition and learned some of the elements of effective language learning. There’s certainly an intangible element to learning a language–it’s often the case that the earlier you learn a language, the better chance you have of achieving true fluency/multilingualism–but it’s also possible to learn a language fairly well as an adult through diligent work. Adults have more honed metacognitive skills and might outperform a child in more formal educational settings. This is hopefully pretty self-evident, since adults would have more experience in formal educational settings and have developed their own methods for learning in a way that a young child hasn’t.

I’m thinking about this second language acquisition class for two reasons: 1) A few weeks ago I had a paper accepted for a conference in Montréal. In a weird desire to prepare myself for traveling in a few months, I decided to try and resurrect my four years of high school French so that I can, at the very least, comprehend the language even when I cannot (and really should not) speak it. I’ve been trying to immerse myself in the French language in a way that I haven’t done in a while.

And 2) When I feel like I’m on the outside of my writing, I try to turn that into a strength. I try to imagine that I’m just trying to learn English again as a second language, even though it is my first, and so far only, language. I say to myself: of course I’m struggling to form a sentence–I’m learning this language over and over again each time I sit down to try and write something new. It doesn’t completely erase the angst and feelings of inadequacy when the words fail to fall onto the page, but it’s something almost like comfort.

Whenever I’ve felt particularly disheartened this semester, I listened to Stromae’s “Santé,” a pop dance song that highlights the often overlooked work of the people who make the world turn, who make the celebrations run smoothly, who are often unseen in the glitz and glam of the moment and are in charge of the cleaning up the detritus after the last guest has left. The first line of the chorus says, “Et si on célébrait ceux qui n’célèbrent pas.” And so we celebrate those who do not celebrate. “Encore une fois, j’aimerais lever mon verre à ceux qui n’en ont pas.” Again, I’d like to raise my glass to those who don’t have one. “Santé” feels like the kind of art I’d like to make with my writing: a body weighed down by a bigger and more important idea, but nonetheless dances joyfully to an upbeat tune.

What is the takeaway from how I’ve spent my time this semester? What lessons did I really learn, in contrast to what I had intended to learn? The semester felt simultaneously quick and interminable. I fell behind on my work almost across the board because the weeks passed by so quickly. But the semester was also so long that I nearly forgot that the first few weeks were a patchwork of days off due to holidays, bad air quality that made me cancel class, and a heat dome that made my walk between classes extremely exhausting. But what have I really learned from all this? What has this semester taught me?

I’m still learning–over and over–what it is I want from life. I’m still figuring out how to spend my time to align with my idea of a good and meaningful life. The words I have often fall short, fumble into cliches. What matters is that I try–again and again–to figure it out. Next semester will be better. (The spring always is.)

-

Ten years after my first story

Yesterday, I was talking to a class about the process of revision after having read Joy Williams’s “Uncanny Singing That Comes from Certain Husks.” I haven’t read very much Joy Williams (I was substituting for a fellow PhD student’s Beginning Creative Writing class, which is how I encountered this essay), but as much as I questioned the essay, I found some uncanny resemblances to the first time I had seriously tried to write a story.

“Whenever the writer writes,” Williams says, “it’s always three o’clock in the morning, it’s always three or four or five o’clock in the morning in his head. Those horrid hours are the writer’s days and nights when he is writing.” My first story was then typed, then written out by hand, then marked with blue pen, then typed from those edited pages before I turned it in for my first creative writing workshop during my third year of undergrad. I took practically all night; I neglected all of my other school work. I don’t remember the feedback people gave me in class. I don’t even really remember believing in my own story–I’m fairly certain I had emailed the professor and asked if she thought my story could be ready to send to my undergrad institution’s literary journal. And after a month or so of preparing myself for rejection (i.e., I forgot about the submission in the heyday of studying abroad), I got an acceptance.

I’ve written before about how that first success overinflated my sense of accomplishment. And when I re-read that story now (because I’m the type of person who will re-read her published writing–I put all that effort into writing a story I want to see in the world that it seems silly not to read it now and then), I think it’s fine for a beginning writer. I can see the places where I avoided using more complex sentence structures simply because I knew I had a tenuous grasp on grammar. The point of view is a little stilted in that it’s consistent but doesn’t feel as vivid as it could be. The structure is plain. The vocabulary is okay; at the very least it avoids being too ostentatious. There are only three characters, one of whom is off the page and present only in the dialogue.

Of course, I was aware of none of this when I was writing that story ten years ago. Ten years (and some months) ago, I was sitting in a dorm room in Sydney, enthralled by the process of going back and forth between page and screen. My room had a tall, skinny window that only opened a little bit to let in fresh air, and every so often the sound of the street lights changing would slip through the still nighttime. Everything in my life was rose-tinted, not even yet retrospective. I didn’t think anything would come of that first story.

In a way, nothing has come from that first story. Very little of the style and almost none of the themes have persisted through the years. I write some stories in the first person now (and only do a little bit of agonizing over whether or not readers would ever believe that I am the narrator). Instead of being semi-autobiographical (my characters in that first story lived in New York City, and I lived in New York City at the time, and so on), I try to remove my stories from my lived experience. There’s also a kind of thoughtlessness to that first story; its concerns are so small that it attempts to avoid being embedded in a social or political context (though no story can avoid being placed in the wider world). Nothing has come from that first story–except all the rest of the writing I’ve done since then.

Maybe the smallness of the story was my “just making contact, contact with other human beings,” as Williams says, after having tried to write a transforming story. Maybe I had tried so hard–stayed up too late–and put all that effort into a story that needed to be small. It was a story about two people. Sometimes that’s enough.

(If you’re curious about the first story I ever got published, you can read it here.)